by Margherita Guarducci

© 1960, Hawthorn Books

(all rights reserved)

| Grottoes

Vatican City Colonnade Saints Floorplan #2 |

|

|

|

|

CONTENTS

Introduction

- H. V. Morton

Preface - The Author

Illustrations

I. THE TESTIMONY OF ANCIENT AUTHORS

II. THE VATICAN IN ANCIENT TIMES

III. THE NECROPOLIS UNDER

THE BASILICA

IV. THE APOSTLES MEMORIAL

V. THE TESTIMONY OF THE

INSCRIPTIONS

VI. THE CULT OF THE APOSTLES PETER

AND PAUL ON THE APPIAN WAY

VII. CONCLUSIONS

The Author and Her Book

III. THE VATICAN IN ANCIENT TIMES

The name "VATICAN" is derived from the Latin adjective Vaticanus, which is derived, in turn, from the noun Vatica or Vaticum. This word is probably of Etruscan origin, a fact which can easily be explained when we consider that the region of the modern Vatican, on the right bank of the Tiber, originally belonged to Etruria, or rather, apparently, to the southernmost of the Etruscan cities, the powerful Veii with which Rome had to struggle so much during its first period of expansion. A memory of the very ancient allegiance of the Vatican to Etruria was still preserved in the first century A.D. Pliny the Elder, the famous naturalist who died in 79 A.D., a victim of the eruption of Vesuvius, tells us of a venerable oak in the Vatican region. An Etruscan inscription in bronze letters declared this oak sacred.1

When Veii fell under the power of the Romans (396 B.C.), the Vatican territory (Plate 1) became part of the city of Rome, although it always remained outside the walls: the so-called Servian walls of the fourth century B.C. and, much later, the walls built by the emperors Aurelianus and Probus - between 270 and 278 A.D. - to defend the city against the fearful invasions of the barbarians. When the Emperor Augustus divided the city into fourteen regions, the Vatican became part of the fourteenth, which included the territory across the Tiber (trans Tiberim).

The Vatican zone was partly a hill and partly a plain. The heights, furrowed by deep gouges and called montes vaticani, are the hills which extend from Monte Mario to the Janiculum. The plain, lying between the hills and the Tiber, corresponds to the modern Prati di Castello, Borghi, Via della Conciliazione and all the right bank of the Tiber as far as the foot of the Janiculum Hill.

The terrain, covered by very permeable rocks through which rain water ran easily, was by nature poor and inhospitable; while the plain was subject to floods and, naturally, infested with malaria. Tacitus, speaking of the Emperor Vitellius' army which was decimated on the Vatican plain in the summer of 69, does not hesitate to call the Vatican region unhealthy (infamibus Vaticani locis).2 Indeed, the Vatican plain was a worthy breeding-ground for snakes and became famous for them. According to Pliny there were snakes there of such enormous size that they were known to swallow babies whole.3 The hilly region was even more poorly adapted for agriculture. Its wines, at least, had the reputation of being terrible, so much so that the poet Martial, in the second half of the first century A.D., compares them sometimes to vinegar, sometimes even to poison.4 Its only resources consisted in some deposits of clay; these supplied many furnaces which turned out bricks, tiles, and some of the "fragile bowls" mentioned by the poet Juvenal (who lived between the first and second centuries A.D.) in one of his Satires.5

Nevertheless, this unhappy region of ancient Rome, during the first century A.D., caught the attention of various wealthy persons who tried to improve its conditions. Agrippina, wife of Germanicus and mother of Emperor Caligula, had gardens planted there; the powerful family of the Domitii had other vast gardens nearby, and in particular Domitia Lepida, Nero's aunt who died in 59 A.D. as a result of poison give to her by her nephew. All these garden zones of green, which came through inheritance into the already immense partrimony of the debauched emperor, formed the vast "Gardens of Nero" (horti Neronis), the same in which, after the burning of Rome, Nero set up emergency housing for a large proportion of the homeless lower classes. Besides the "Gardens of Nero," there were also, perhaps, the very extensive gardens of M. Aquilius Regulus. We know, from an epistle of Pliny the Younger,6 that this ambitious, plotting, cruel man, who lived from the time of Nero to the first years of Trajan, owned vast territories on the other side of the Tiber, arranged as gardens and adorned with large porticos and, on the river's bank, many statues. These gardens may have been located in the Vatican region.

It would be an error to think that this vast area was completely covered by true and proper gardens with rows of flowers, fountains, statues, and cages full of vari-colored birds. The region near the Tiber may have looked something like that, but the rest of the plain and the montes vaticani must have included large stretches of fields, forests and even sterile, uncultivated patches.

A territory this large would naturally have its streets and, in some places, buildings. The Vatican streets were named the Via Cornelia, the Via Aurelia and the Via Triumphalis, which all began at the Tiber and led to the heights. The so-called "Bridge of Nero," whose remains can still be seen near the modern Ponte Vittorio Emanuele, gave access to these streets. The name "Bridge of Nero" does not date back to Nero's time, but this is no reason to deny its accuracy. It is very probable that Nero, who owned extensive gardens in the Vatican area, would have a bridge built to connect this property with the rest of Rome. And it is equally probable that even before Nero's time, a bridge (perhaps a wooden rather than a stone one) crossed the Tiber at this point. In 134 A.D., Nero's bridge was joined by the Elian Bridge, whose purpose was to give access from the other side of the Tiber to the grandiose mausoleum of the Emperor Hadrian, now known as the Castel Sant' Angelo.

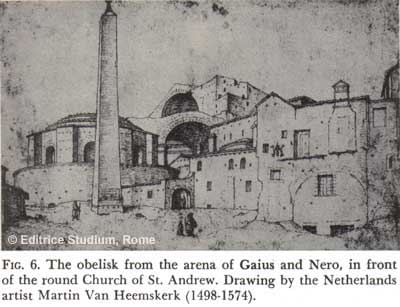

The most noteworthy structure on the Vatican plain was an arena built by the Emperor Gaius (i.e., Caligula: 37-41 A.D.) and improved by Nero (54-68 A.D.) and therefore known to the Romans as the circus Gai et Neronis. Caligula's successor, the Emperor Claudius, staged races and hunting shows in this arena several times, and Nero also used it quite frequently. Wishing to show the people his ability as a charioteer, as Tacitus informs us,7 he enjoyed steering his horses in the "space marked off on the Vatican plain," that is, evidently, in the Vatican arena. In this same arena he staged the famous and very cruel spectacles which took the lives of so many Christian martyrs, among them, as we have reason to believe, St. Peter himself.8 The chief landmark of the arena was the obelisk which Caligula had brought directly from Egypt on a ship, so beautiful that, according to Pliny, its equal had never before been seen.9 This obelisk, we learn through an inscription dedicating it to the deceased emperors Augustus and Tiberius,10 is the same that stands today in the center of St. Peter's Square. However, this is not its original location. We know that it was formerly located near the southern wall of the basilica, close to the modern Sacristy, and that in 1586, during the reign of Pope Sixtus V, it was moved by the architect Domenico Fontana into the center of the great square. This was a memorable project and its extreme difficulty led to some moments of drama. The record of this undertaking is preserved for us by a stone placed in the pavement at the spot from which the obelisk was taken.

But where, exactly, was the arena of Gaius and Nero in antiquity? Some scholars, thinking that the stone truly marks the original location of the obelisk and that it must have been located in the center of the arena, that is, at the middle of the so-called spina (dividing wall), believe that the oval area of the arena itself must have lain parallel to the Basilica of St. Peter. Others, although they admit that the obelisk was originally located on the spot indicated by the stone, do not find it necessary to believe that this spot was the center of the arena. Finally, there are others who believe that the obelisk was moved once before in ancient times, and that therefore the stone near the Sacristy merely indicates its second location, not its original site.

Recent excavations near the Sacristy have shown that this was, most probably, the original location of the obelisk. And it is difficult to believe that the obelisk would not have been placed on the spina in the arena, since the information we have on the structure of ancient arenas (for example, the largest arena in Rome, the Circus Maximus) show an almost universal custom of placing an obelisk right on the spina. It is very probable, therefore, that Nero's arena had its axis parallel to that of the future Basilica of St. Peter, with an opening toward the heights presently occupied by the Vatican Gardens. The nature of the terrain, which forms a small valley at this spot, would have naturally suggested the erection of an arena.

Except

for the obelisk, no remains of the arena have come to light so far, but

in this area the excavations have not gone so deep that we can say there

are no traces. Besides, it is tenable that stone walls formed only part

of the arena; the rest might have been formed of wooden panels or even

of walls of vegetation, as was sometimes done during that period. At any

rate, the existence of the arena in that area of the Vatican is proven

by an epigraph found during the recent excavations under the basilica.

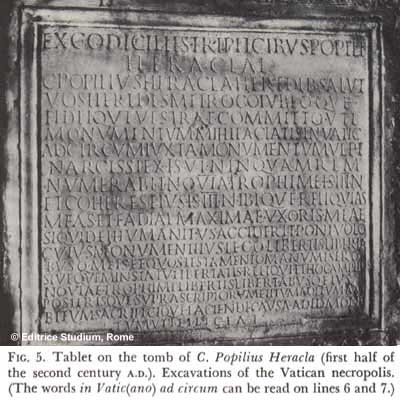

The evidence is a marble tablet placed on the door of a sepulcher; the

inscription on the tablet state that a certain C. Popilius Heracla had

required his heirs to bury him in a mausoleum "in the Vatican near the

arena" (in Vaticano ad circum) (Fig. 5). Since the mausoleum in which

the heirs placed the remains of their benefactor is certainly that which

the excavations discovered, we can deduce with certitude that the arena

was in the immediate vicinity. And if we accept the very probable theory

that the obelisk was formerly right on the spina of the arena, it is necessary

to maintain that at the termination of the second century A.D. the arena

was no longer used, since, to the West of the obelisk and right next to

it, on a higher level, a circular-shaped tomb was built whose walls can

be dated in the time of the Emperor Caracalla (211-217 A.D.). This tomb

was later transformed into a church dedicated to St. Andrew (Fig. 7).

The construction of this building on the site of the arena informs us

that the arena no longer existed.

Except

for the obelisk, no remains of the arena have come to light so far, but

in this area the excavations have not gone so deep that we can say there

are no traces. Besides, it is tenable that stone walls formed only part

of the arena; the rest might have been formed of wooden panels or even

of walls of vegetation, as was sometimes done during that period. At any

rate, the existence of the arena in that area of the Vatican is proven

by an epigraph found during the recent excavations under the basilica.

The evidence is a marble tablet placed on the door of a sepulcher; the

inscription on the tablet state that a certain C. Popilius Heracla had

required his heirs to bury him in a mausoleum "in the Vatican near the

arena" (in Vaticano ad circum) (Fig. 5). Since the mausoleum in which

the heirs placed the remains of their benefactor is certainly that which

the excavations discovered, we can deduce with certitude that the arena

was in the immediate vicinity. And if we accept the very probable theory

that the obelisk was formerly right on the spina of the arena, it is necessary

to maintain that at the termination of the second century A.D. the arena

was no longer used, since, to the West of the obelisk and right next to

it, on a higher level, a circular-shaped tomb was built whose walls can

be dated in the time of the Emperor Caracalla (211-217 A.D.). This tomb

was later transformed into a church dedicated to St. Andrew (Fig. 7).

The construction of this building on the site of the arena informs us

that the arena no longer existed.

Besides

the arena of Gaius and Nero, there was another place on the Vatican plain

used for races; the Gaianum, named for the same Emperor Gaius (i.e., Caligula),

and recorded by Dio Cassius, the Greek historian of Rome, who lived between

the second and third centuries after Christ, as a "place" (![]() -chorion) where contests of horses were held.11 Its location

is still uncertain. Some scholars locate the Gaianum near Hadrian's tomb,

others prefer to place it near the modern Via dell Conciliazione, noting

that in that area, and more exactly in the neighborhood off the church

of Santa Maria in Traspontina, many charioteers' inscriptions have been

found. At any rate, the report according to which the dissolute and extravagant

Emperor Heliogabalus (218-222) once drove four teams of elephants on the

Vatican plain, ruining the tombs in the area with his bad joke, probably

refers not to the area of Gaius and Nero but to the Gaianum.12

It is hard to believe that anyone could drive four teams of elephants

in the relatively restricted space of Nero's arena, not to mention the

fact that in the time of Heliogabalus the arena must have been long out

of use.

-chorion) where contests of horses were held.11 Its location

is still uncertain. Some scholars locate the Gaianum near Hadrian's tomb,

others prefer to place it near the modern Via dell Conciliazione, noting

that in that area, and more exactly in the neighborhood off the church

of Santa Maria in Traspontina, many charioteers' inscriptions have been

found. At any rate, the report according to which the dissolute and extravagant

Emperor Heliogabalus (218-222) once drove four teams of elephants on the

Vatican plain, ruining the tombs in the area with his bad joke, probably

refers not to the area of Gaius and Nero but to the Gaianum.12

It is hard to believe that anyone could drive four teams of elephants

in the relatively restricted space of Nero's arena, not to mention the

fact that in the time of Heliogabalus the arena must have been long out

of use.

For

those who enjoyed sea spectacles, the Vatican plain also offered the Naumachia,

that is, a place set aside for the representation of naval battles.13

The location of the Naumachia cannot be pointed out exactly; it is possible

only to connect it with the medieval name of the chapel of San Pellegrino

in Naumachia, located in the region of the modern Vatican City.

For

those who enjoyed sea spectacles, the Vatican plain also offered the Naumachia,

that is, a place set aside for the representation of naval battles.13

The location of the Naumachia cannot be pointed out exactly; it is possible

only to connect it with the medieval name of the chapel of San Pellegrino

in Naumachia, located in the region of the modern Vatican City.

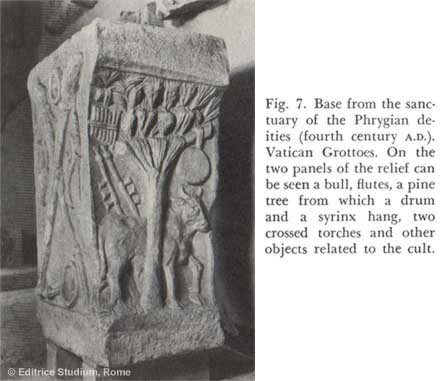

With

the gardens and the places of spectacle there was also a sanctuary: the

Phrygianum, i.e., a place where the Phrygian divinities Cybele and Attis

were honored. The first center of this cult in Rome was established on

the Palatine, the most ancient of the seven hills, to commemorate the

tradition according to which Aeneas, the progenitor of the Romans, came

to the strands of Latium after his exile from Phrygian Troy. But another

cult of Cybele and Attis settled later, outside the city's walls, right

on the Vatican plain. The most ancient record we have of the Vatican Phrygianum

is in an epigraph from 160 A.D.,14 but it is very probable

that the foundation off the sanctuary goes back to a more remote time.

Its location cannot be established with perfect accuracy; but it is very

probable that it was in the immediate vicinity of Nero's arena, near the

modern Arco delle Campane. This seems proven by many foundations found

in this area bearing reliefs and inscriptions referring to the characteristic

cult of the Phrygian divinities (Fig. 7). In the various reliefs we find,

besides the typical hat of Attis, bulls, sheep, pine trees, torches, flutes,

reed pipes, drums and tambourines; all images which speak for themselves.

The inscriptions also tell us of taurobolia, i.e., sacrificies of bull

which were - we might mention -  the

culminating act of these horrid and mysterious rites.15 The

cult of Attis and Cybele in the Vatican lasted a long time, almost throughout

the fourth century A.D., when the basilica built by Constantine to honor

Peter already stood nearby. But we have reason to believe that the celebration

of these bloody rites was suspended for a fairly long period during the

fourth century, not only because these rites were far removed from the

spirituality Christianity, now publicly professed throughout the Empire,

but also because the Phrygianum was in the middle of the storage-yard

for the construction of the basilica. The dates found on the inscriptions

recording the taurobolia are therefore very valuable in helping to establish

the chronology of Constantine's basilica, and permit us to fix the beginning

of construction around 322 A.D.16

the

culminating act of these horrid and mysterious rites.15 The

cult of Attis and Cybele in the Vatican lasted a long time, almost throughout

the fourth century A.D., when the basilica built by Constantine to honor

Peter already stood nearby. But we have reason to believe that the celebration

of these bloody rites was suspended for a fairly long period during the

fourth century, not only because these rites were far removed from the

spirituality Christianity, now publicly professed throughout the Empire,

but also because the Phrygianum was in the middle of the storage-yard

for the construction of the basilica. The dates found on the inscriptions

recording the taurobolia are therefore very valuable in helping to establish

the chronology of Constantine's basilica, and permit us to fix the beginning

of construction around 322 A.D.16

The Liber Pontificalis, whose first version goes back to the sixth century, asserts that Peter was buried "near the temple of Apollo" and specifies that this "temple of Apollo" was in the Vatican, near "Nero's palace."17 Since we must certainly identify "Nero's palace" with the ruins of the famous arena, the temple of Apollo must have been very near the present basilica or precisely in the area which it covers. But scholars' attempts to track down the remains of the temple of Apollo have been so far unsuccessful and will probably remain so, since it is quite possible that the statement in the Liber Pontificalis may be unfounded and the temple of Apollo may never have existed.

There were also tombs in the ancient Vatican region. At first, the presence of tombs close to gardens and places of amusement such as the arena, the Gaianum, and the Naumachia, may seem strange; but on further reflection it is easy to recognize that our reluctance to mingle life and death by burying the dead next to places where living is most intense derives from a modern concept far from the mentality of the ancients. The Romans of the imperial age did not have this kind of attitude and saw nothing wrong in laying their dead to rest where the survivors dwelt or sought amusement. For example, it is sufficient to recall that on the Appian Way the rich villa of the Quintilii stands out flanked by tombs and that in "Caesar's gardens" on the right bank of the Tiber there are tombs right next to other buildings that have nothing funereal about them.

Students

of Roman topography know that for the ancient Romans the sides of highways

were favorite burial places. Thus, long lines of tombs, decorated with

varying degrees of ostentation, bordered not only the Appian Way but also

the Via Latina, the Via Prenestina and all the great arteries which radiated

from the City to the near and far places of the world dominated by Rome.

Sometimes the tombs were so close together that they formed cemeteries.

The same thing happened, and it was natural that is should happen, along

the streets of the Vatican region.

Students

of Roman topography know that for the ancient Romans the sides of highways

were favorite burial places. Thus, long lines of tombs, decorated with

varying degrees of ostentation, bordered not only the Appian Way but also

the Via Latina, the Via Prenestina and all the great arteries which radiated

from the City to the near and far places of the world dominated by Rome.

Sometimes the tombs were so close together that they formed cemeteries.

The same thing happened, and it was natural that is should happen, along

the streets of the Vatican region.

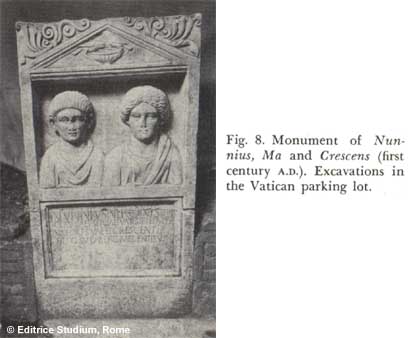

Many years ago, sporadic excavations had already shown the existence of an ancient burial place along the Via Triumphalis and its various side streets, i.e., in the area between the Vatican Palaces and the modern Piazza Risorgimento. A recent excavation, executed systematically in the Vatican City, in the place where the parking lot now stands, has confirmed the existence of this necropolis, bringing to light some tombs of very great interest and showing that the greatest growth of the necropolis took place in the first century A.D. Among other documents, one that stands out is the beautiful monument which a certain Nunnius, a slave of Nero, had made for himself, his wife who had the rare name Ma, and his son Crescens (Fig. 8).

This

large and important burial place extended across the northeastern slope

of the hill on which the Vatican Palaces are built. But even on the southern

slope, along the Via Cornelia and its side streets, there were tombs.

A notable part of them, which I shall discuss later at greater length,

came to light during excavations under St. Peter's Basilica. Other tombs

were located, more to the west, behind the apse of the basilica, in the

place now occupied by the chapel of St. Stephen of the Abyssinians; still

others, more to the east, in front of the basilica. In all probability,

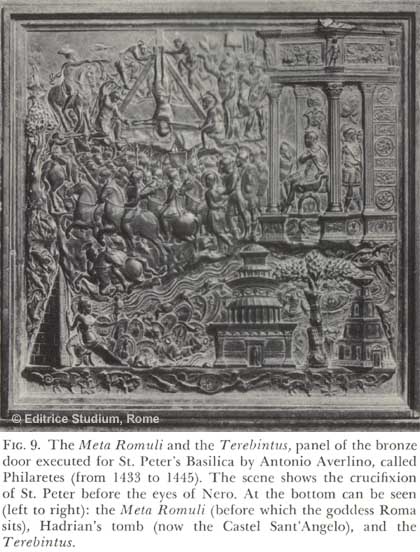

two funeral monuments which were well-known in the Middle Ages and have

since been destroyed, the so-called Meta Romuli and the Terebintus belonged

to this row of tombs (Fig. 9). The first structure, considered by popular

imagination to be the tomb of Romulus, founder of Rome, was a building

in the form of a pyramid, covered by large marble slabs which were used

in the seventh century to beautify the atrium of St. Peter's; the second,

called Terebintus (a deformation of Tiburtinus) from the stone of Tivoli

(travertino) which had been used in its construction, was circular in

from.

This

large and important burial place extended across the northeastern slope

of the hill on which the Vatican Palaces are built. But even on the southern

slope, along the Via Cornelia and its side streets, there were tombs.

A notable part of them, which I shall discuss later at greater length,

came to light during excavations under St. Peter's Basilica. Other tombs

were located, more to the west, behind the apse of the basilica, in the

place now occupied by the chapel of St. Stephen of the Abyssinians; still

others, more to the east, in front of the basilica. In all probability,

two funeral monuments which were well-known in the Middle Ages and have

since been destroyed, the so-called Meta Romuli and the Terebintus belonged

to this row of tombs (Fig. 9). The first structure, considered by popular

imagination to be the tomb of Romulus, founder of Rome, was a building

in the form of a pyramid, covered by large marble slabs which were used

in the seventh century to beautify the atrium of St. Peter's; the second,

called Terebintus (a deformation of Tiburtinus) from the stone of Tivoli

(travertino) which had been used in its construction, was circular in

from.

The

rich tombs discovered under St. Peter's Basilica are not older than 130

A.D., approximately, and this discovery by the excavators has some importance

in studying the question of St. Peter's tomb. Indeed, some scholars, noting

the absence of first-century tombs in this area, have found the fact sufficient

to deny point-blank the presence of the Apostle's tomb. But further investigations

have shown that some tombs were there even in the first century.18

The Meta Romuli, with its pyramidal form similar to that of the well known

pyramid of Gaius Cestius on the Via Ostiense (which, by the way, was taken

for the tomb of Remus in the Middle Ages), seems to have been a first-century

structure, very suitable to the taste of the times in which Roman emperors,

deeply  interested

in Egyptian things, were bringing venerable obelisks to Rome and encouraging

the imitation of Egyptian styles. A group of first-century tombs must

have existed on the site of the present chapel of St. Stephen of the Abyssinians.

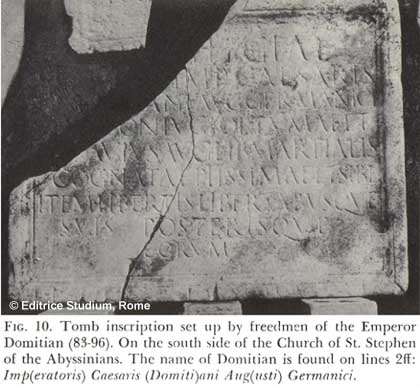

This fact is demonstrated by a funeral inscription (Fig. 10) set up by

freed slaves of the Emperor Domitian between 83 and 96 A.D. and other

documents which can be dated either in the time of the Flavii (69-96)

or even in earlier times. Other first-century tombs have also been found

in the area of the modern St. Peter's Square and near the southern side

of the basilica. Thus, we can establish the existence of a line of first-century

tombs which leaves the Tiber, follows the route of the modern Via della

Conciliazione, crosses St. Peter's Square and, passing under the basilica,

reaches the site of St. Stephen of the Abyssinians and the slopes of the

Vatican hills.

interested

in Egyptian things, were bringing venerable obelisks to Rome and encouraging

the imitation of Egyptian styles. A group of first-century tombs must

have existed on the site of the present chapel of St. Stephen of the Abyssinians.

This fact is demonstrated by a funeral inscription (Fig. 10) set up by

freed slaves of the Emperor Domitian between 83 and 96 A.D. and other

documents which can be dated either in the time of the Flavii (69-96)

or even in earlier times. Other first-century tombs have also been found

in the area of the modern St. Peter's Square and near the southern side

of the basilica. Thus, we can establish the existence of a line of first-century

tombs which leaves the Tiber, follows the route of the modern Via della

Conciliazione, crosses St. Peter's Square and, passing under the basilica,

reaches the site of St. Stephen of the Abyssinians and the slopes of the

Vatican hills.

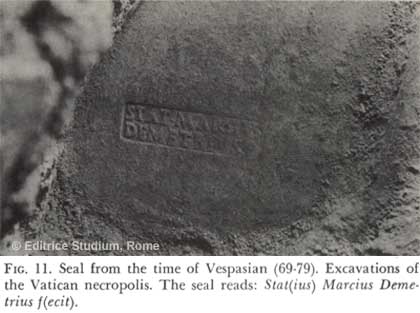

In

opposition to those scholars who have denied the existence of first-century

tombs under the basilica, we can state with certitude today that there

were first-century tombs there. From earlier excavations one tomb was

already known, covered with tiles among which was one with the manufacturer's

mark (Fig. 11) datable in the reign of the Emperor Vespasian (69-79).19

It was possible to object (and naturally some did object) that this single

tile might have been second-hand, and therefore taken from somewhere else.

But now new proof has been added to the marked tile, and it is even more

conclusive: a small lamp also marked and found in a place close to the

tomb bearing the mark from the time of Vespasian. The lamp is made of

terra cotta and belonged to a tomb, a fact deduced from the presence of

burned bones and other fragmentary objects related to funeral rites: pieces

of another lamp, vases, glasses, etc. The presence of burned bones and

of many pieces of ash indicates that the tomb to which the inscribed lamp

belonged was used for cremation and that the funeral material in its vicinity

was the contents of a crematory furnace (ustrinum). Now, our lamp is marked

with the name of the potter L. Munatius Threptus. The same mark occurs

on many other lamps, two of which can be dated with certitude in the first

century, thanks to a lucky discovery. Some of these lamps were found in

the tomb of the Statilii near the Porta Maggiore, which was closed in

the time of Statilia Messalina, third wife of Nero, about 70 A.D. It follows

that the lamp found under the basilica of St. Peter belongs to the first

century, and this conclusion is confirmed by the examination of other

funeral materials found in the vicinity which can also be dated in the

first century.

In

opposition to those scholars who have denied the existence of first-century

tombs under the basilica, we can state with certitude today that there

were first-century tombs there. From earlier excavations one tomb was

already known, covered with tiles among which was one with the manufacturer's

mark (Fig. 11) datable in the reign of the Emperor Vespasian (69-79).19

It was possible to object (and naturally some did object) that this single

tile might have been second-hand, and therefore taken from somewhere else.

But now new proof has been added to the marked tile, and it is even more

conclusive: a small lamp also marked and found in a place close to the

tomb bearing the mark from the time of Vespasian. The lamp is made of

terra cotta and belonged to a tomb, a fact deduced from the presence of

burned bones and other fragmentary objects related to funeral rites: pieces

of another lamp, vases, glasses, etc. The presence of burned bones and

of many pieces of ash indicates that the tomb to which the inscribed lamp

belonged was used for cremation and that the funeral material in its vicinity

was the contents of a crematory furnace (ustrinum). Now, our lamp is marked

with the name of the potter L. Munatius Threptus. The same mark occurs

on many other lamps, two of which can be dated with certitude in the first

century, thanks to a lucky discovery. Some of these lamps were found in

the tomb of the Statilii near the Porta Maggiore, which was closed in

the time of Statilia Messalina, third wife of Nero, about 70 A.D. It follows

that the lamp found under the basilica of St. Peter belongs to the first

century, and this conclusion is confirmed by the examination of other

funeral materials found in the vicinity which can also be dated in the

first century.

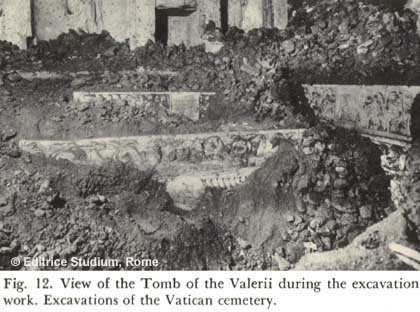

In

conclusion, it is evident that burials did take place, during the time

of St. Peter, in the area where later a basilica was to be built in his

honor. Thus, the location of the Apostle's tomb in the place where tradition

would have it, is not, in itself, a strange or anachronistic idea. There

were probably no large, rich mausoleums in this part of the Vatican plain

during the first century. These were built in great numbers during the

following century, changing radically the aspect of the region. In the

first century, there must have been only poor and meager tombs, with barely

the width of a street (evidently the Via Cornelia) separating them from

the neighboring arena of Gaius and Nero. They were the tombs of poor people,

and among them the tomb of the Fisherman from Galilee could easily have

found its place.

In

conclusion, it is evident that burials did take place, during the time

of St. Peter, in the area where later a basilica was to be built in his

honor. Thus, the location of the Apostle's tomb in the place where tradition

would have it, is not, in itself, a strange or anachronistic idea. There

were probably no large, rich mausoleums in this part of the Vatican plain

during the first century. These were built in great numbers during the

following century, changing radically the aspect of the region. In the

first century, there must have been only poor and meager tombs, with barely

the width of a street (evidently the Via Cornelia) separating them from

the neighboring arena of Gaius and Nero. They were the tombs of poor people,

and among them the tomb of the Fisherman from Galilee could easily have

found its place.