The First Full Account of the Search for the Apostle's Body

by John Evangelist Walsh

© 1982, Doubleday & Co.

(all rights reserved, this material should not be copied)

| Grottoes

Vatican City Colonnade Saints Floorplan #2 |

|

Related Items To Buy this

Book |

|

|

1. BURIED TOMBS

2. STREET OF THE DEAD

3. BENEATH THE HIGH ALTAR

4. PETER'S GRAVE

5. THE RED WALL COMPLEX

6. STROKE OF FATE

7. THE WOODEN BOX

8. WHAT THE GRAFFITI HID

9. THE BONES EXAMINED

10. THE PETER THEORY

11. DECISION

12. THE ANCIENT SILENCE

Appendices

I

Buried Tombs

The great central aisle of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, awesomely flanked by a parade of massive pillars, adorned with monumental statuary, stretches nearly four hundred feet from the main entrance before reaching the majestic high altar, just under the tiered magnificence of the soaring dome. Proportioned on a truly gigantic scale, this renowned promenade offers an unforgettable, soul-stirring vista unmatched anywhere in the world. Like a reverse image of these sweeping splendors, one level below the lustrous marble pavement of the central aisle there lies the cavernous burial crypt known as the Sacred Grottoes. It was in the somber atmosphere of this lower level that the search for St. Peter began, but entirely by accident. At the start there was no hint that a journey back through the ages, even to the morning of Christianity, was imminent.

A long, unusually low-ceilinged chamber, the Grottoes were divided into three broad aisles by a series of squat archways. Sunk into the main walls on either side were the open-fronted crypts in which rested the ornate sarcophagi of many illustrious dead. Among them were the tenth-century emperor of Germany, Otto II, the only English pope, Hadrian IV, who reigned in the twelfth century, Queen Christina of Sweden, and James II of England. It was another burial, that of Pope Pius XI, who died in February 1939, and the alterations needed for his interment, that caused the first extensive change in the area after it had lain undisturbed for centuries. Soon after the Pope's burial it was decided that the Grottoes should be converted to a more practical use, made over into a subterranean chapel. Long contemplated, the move had always before, for one reason or another, been postponed.

Ponderously vaulted, the low-slung ceiling of the Grottoes, allowing only an irregular eight feet or so of headroom, presented the renovators with their first major problem. As the only feasible, it was decided to lover the level of the entire floor, or most of it, by some three feet. This proved a formidable task, calling for a prodigious amount of labor, and for several weeks the rude sounds of sledgehammer, crowbar, and winch filled the brooding chamber. At length, when a sufficient portion of the heavy marble pavement and its underpinning had been taken up, the diggers moved in.

Almost immediately the workmen's shovels probing the underlying soil began to uncover a random series of marble and stone sarcophagi, some small and plain, others large and impressively ornamented. These were recognized as burials which had been let down through the flooring at various times in the distant past and they were lifted out for disposal elsewhere, with the older and more interesting ones being set aside for study.

Operations had been in progress for perhaps three months when a digger, starting work on a new location in the south aisle, reported an unusual find. About two feet down he had struck what appeared to be the ragged top of a brick wall. More than a foot thick, it descended into the hard-packed earth to an unknown depth. One side was plain reddish brick, somewhat weathered. The other side held a plaster facing painted a rich greenish-blue.

Under the watchful eye of a Vatican archaeologist, hastily summoned, the whole length of the wall along the surface was laid bare, and it was seen to form one side of a large quadrangle, twenty-two feet by twenty. Even a cursory look showed that the find promised to be exciting: the walls undoubtedly formed the top of a small building, but the whole roof had been roughly sheared off, and the remaining shell had been rammed full of earth. The brickwork, judging by its form and layering, was extremely ancient.

Guided by the archaeologist, diggers began emptying the little building of its burden of packed soil and slowly, foot by foot, the level dropped, gradually revealing more of the greenish-blue plaster. Farther down there came to light an elaborate arrangement of wall niches, some holding cremation urns. The building was a tomb.

All of the niches, most of them roundheaded with scallop-shell designs, were painted a dark purple and framed by diminutive white columns, while a contrasting bright red overspread the adjacent surfaces. Floral decorations, daintily modeled in white stucco, clung to the walls, in some places with stucco dolphins sporting among the flowers. In the upper portion of one large semidomed niche there was a painting, well executed though somewhat damaged, of Venus rising from the sea. Another niche held a picture of an ox and a ram at rest in an idyllic landscape, and in still another there was a miniature stucco frieze, strung on a scarlet background, or cranes and pygmies. Everywhere the walls were adorned with a masterful display of pediments, paneling, apses, and entablatures. The entrance doorway, still elegantly framed by fine slabs of travertine (dressed limestone), faced squarely toward the south side of the basilica. The tomb itself, in its entirety, sat a little to the left of the basilica's longer axis.

After the diggers had removed most of the earth from the tomb's interior, some six thousand cubic feet of it, the floor was reached, fifteen feet down, and here a touching discovery was made. While all of the formal burials in the mausoleum had proved to be cremations, and thus of pagans - at least a dozen inscriptions were ranged along the walls - laid into the floor was an oblong marble slab which told the excavators that they had come upon the grave of a Christian.

In the grave, declared the Latin epitaph inscribed on the slab, lay the body of a woman named Aemelia Gorgonia, a beloved wife who had been remarkable both for beauty and for innocence, and who had died young. Her age was given as twenty-eight years, two months, and twenty-eight days. The words dormit in pace appeared, using the earliest, and now long-forgotten form o the familiar requiescat in pace. Someone, perhaps the bereaved husband himself, had painstakingly scratched a simple scene into the upper left corner of the slab, showing a woman with a bottle about to draw water from a well. Above the sketch were cut the words anima dulcis Gorgonia (sweet-souled Gorgonia). Together, the words and the drawing, a familiar motif in early Christianity, expressed the firm belief that the lamented woman was enjoying the refreshment of heavenly repose.

A little later, while the workmen were clearing earth from the outside of the tomb, they came upon another isolated burial, this time of a high-ranking woman. On the ground against the front wall, just to the left of the door, lay a large sarcophagus, richly carved from costly Proconnesian marble. The inscription identified the body within as that of a certain Ostoria Chelidon, wife of an Imperial official and daughter of a Roman senator who had filled the high post of "consul designatus."

Gently raising the heavy lid, which was loosely placed, the searchers saw lying in the shallow trough the partially decayed remains of a skeleton. Around the skull, like filigree, were traces of a golden netting, and clinging to some of the bones of the lower limbs were pieces of moldering purple fabric (a color reserved by Roman law for the apparel of the ruling class). Encircling the bones of the left wrist, glinting in the light of the searchers' lamps, was a thick bracelet, apparently of pure gold. As the men gazed at the pitiful remains, which must once have presented a truly splendid appearance, they could not help drawing a contrast with the simple joy which still clung like an aura round the unassuming grave of the young Christian wife. In a hush they replaced the lid, thinking that for so important a burial the casual location was strange. But there was no clue to explain it.

The age of the large tomb was soon determined, causing some astonishment. It had been built sometime in a twenty-year period centering on A.D. 150, and had been in use for almost two hundred years. According to the numerous inscriptions, it was the property of a family named Caetennius, members of Rome's freedman class and evidently of some wealth. While the earliest burials, those in the urns, were all cremations, it was found that at a later stage some bodies, in terracotta coffins, had been laid into arched recesses along the bottoms of the walls. This agreed with the known fact that burials among the pagans of Rome during the third century, accompanying a vague but growing belief in an afterlife, had gradually altered from cremation to inhumation.

Standing in the cleared interior of the tomb, gazing up in wonder at its gorgeously decorated walls, which were now a good deal chipped and faded, the Vatican archaeologists felt a justifiable pride, even excitement. An accident of fate had enabled them to recover what was clearly one of the rarest, best preserved examples of funerary architecture remaining from the height of Rome's golden age. It was a prize well worth the months of effort, one which was bound to yield much valuable information after study by specialists. Meantime, it was thought, the workmen could be returned to the original task of lowering the Grotto floor.

But the discoveries under the basilica were only beginning. Diggers working around the exterior of the Caetennius tomb in order to free it completely, had uncovered new walls. On either side, it was certain, there stood another mausoleum, each also roofless and packed with earth.

While the size and splendor of the excavated tomb, and its age, had prompted some amazement, its mere presence under St. Peter's had not been a complete surprise. That pagan burials of some kind lay under the basilica had long been believed, and there existed support for the claim in the Vatican's old records, where accidental discoveries, made while altering or repairing the church's interior, had occasionally been reported. These early finds, however, had all come long before there was any real understanding of archaeology, or even any interest in the subject. The old reports, colored by the intensely personal views and hearsay evidence of a more impressionable age, offered scant description and few details. Never closely studied, such haphazard discoveries had gone unvalued for whatever information they might yield about the past.

|

|

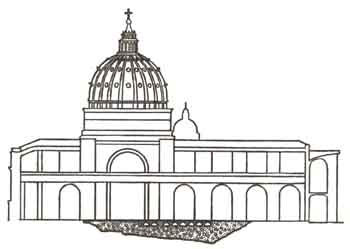

1. Side view

of the basilica showing approximate extent and depth of the excavations.

The slope from left to right follows the ancient line of Vatican

Hill. |

One seventeenth-century tale, for instance, told of a large marble sarcophagus, sumptuously carved, which had been dug up in the vicinity of the high altar. Its occupant had proved to be one Flavius Agricola, whose figure in bas-relief reclined full-length on the heavy lid. There was also a long inscription in Agricola's advice to those he had left behind. "Mix the wine, drink deep," it said in part, "and do not refuse to pretty girls the sweets of love, for when death comes earth and fire devour everything." So offended were the authorities by this blatantly pagan sentiment that they promptly had the lid smashed to pieces and thrown into the Tiber.

Another old story, relating to some floor alterations in the year 1574, told how workmen accidentally broke through the top of some vaulted brickwork to find a diminutive pagan tomb. The walls and ceiling, supposedly, were entirely decorated with a beautiful mosaic of gold, and there was a picture which showed a wonderful pair of prancing white horses. Earth and bones filled the lower half of the chamber, and atop the dirt was a slab of marble on which lay a human body covered with quicklime. After a hasty look the intruders had withdrawn. The body was left undisturbed, the opening closed and the tomb given back to the darkness.

Taken together, the old accounts strongly suggested that beneath the modern edifice there lay an actual pagan graveyard, though indeterminate in nature, extent, and date. If this were true, it had always been thought, especially if any of the burials had been the first occupants of the site, then they would have to be very ancient indeed.

The large tract of land that today lies hidden beneath St. Peter's Basilica - in the old Roman district known as Vaticanum - has been sealed off from human sight for more than sixteen hundred years. About A.D. 330, only two decades or so after the Emperor Constantine issued his Edict of Milan, by which he ended the persecution of the infant church, the land was covered by a huge Roman basilica. No doubts have ever existed as to the purpose of this splendid structure - it was built to honor and preserve what was confidently believed to be the true grave of Simon Peter, Prince of Apostles. Constantine himself, though he was at that period more concerned with the plans for his new capital at Constantinople, took a symbolic part in the work, going so far as to carry on his shoulders twelve baskets of earth-fill, one for each of the apostles.

Thereafter, for the remarkable span of well over a thousand years, Old St. Peter's stood as the acknowledged focus of world Christianity. Annually, down through those centuries, the grave-shrine continued to draw an unfailing and ever-growing throng of the faithful on pilgrimage, a phenomenon unlike anything previously known in antiquity. Then, in the sixteenth century, its very fabric grown decrepit beyond further repair, the venerable structure was taken down, stone by stone. In its place, even while the work of demolition proceeded, there slowly arose - more than a century was for completion - an even larger and grander monument, the present basilica with its breath-taking proportions and majestic dome.

Only where digging was necessary to sink foundations for the massive pillars and the enormous walls had the builders of the new church interfered with the original ground. The subterranean grave of Peter, deep beneath the high altar, they had scrupulously avoided. Aboveground, the shrine's superstructure was redesigned, and a more imposing high altar was installed atop a broad, stepped platform. Looming in classic grandeur over the new high altar there rose an elaborate metal canopy carried on four immense pillars, each of which was cunningly twisted along its length so that it resembled a stack of barley sugar.

The floor of the new basilica's central aisle was raised well above the old one, and it was at this time that the Sacred Grottoes were formed on the lower level. Thus, while Constantine's church had completely disappeared aboveground, at no time had there been any wholesale intrusion on the sequestered precincts below. Whatever was buried under the first basilica in the fourth century - no actual record had come down to the present - must still lie there for the most part undisturbed in the twentieth.